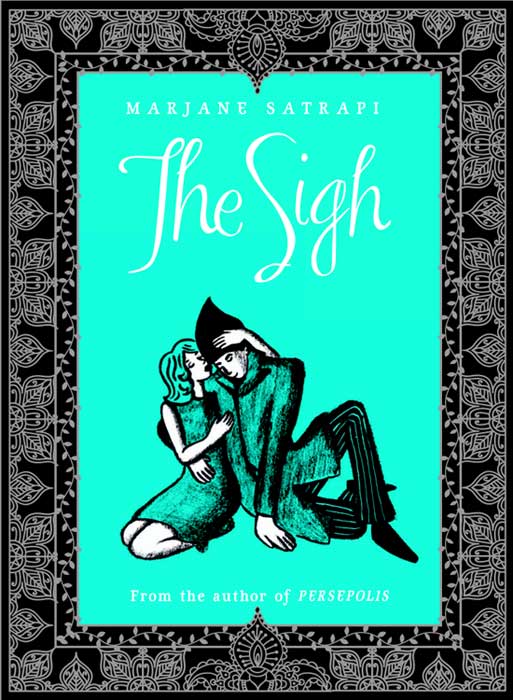

The Sigh

The Sigh

written and drawn by Marjane Satrapi

translated by Edward Gauvin

Archaia / $10.95 / 56 pages

Fairy tales have not traditionally rewarded curiosity. Curiosity, as we know, was the thing that killed the cat and, in fairy tales, it’s the thing that, if not kills them, gets our protagonists in deep trouble. Make a woman or girl the curious one and you’ve got the recipe for some of the grimmest fairy tales. Think Little Red Riding Hood’s naive belief that she can walk alone through the woods or the stolen wife’s unrestrainable desire to discover what lies beyond the forbidden door in Bluebeard (or, in my version, Fitcher’s Bird).

Not much good, fairy tales tell us, comes from women being too curious.

Happily, we have Marjane Satrapi to say otherwise, as she does in her new book, The Sigh. Satrapi, the author of Persepolis and Chicken With Plums, inverts the standard fairy tale formula where curiosity leads to trouble and the world is a dark and dangerous place. In The Sigh, the world she conceives of is much more complex, one in which simple curiosity, neither good nor bad, can lead to both great sorrow and great joy.

(Some spoilers ahead. Read on at your peril. See how curiosity can get you in trouble?)

The Sigh, which is illustrated text (in keeping with the fairy-tale theme) and not a comic, begins with the protagonist, Rose, being disappointed by her father. Upon returning from a business trip, he fails to bring back the present he promised, which causes Rose to sigh. That act summons a creature called Ah The Sigh, a floating, ghostly being who offers Rose’s father the present, which the father accepts, promising Ah anything he wants. As everyone but, apparently her father expects, Ah returns a year later and whisks Rose away.

While this seems like standard fairy tale fare, what comes next is where Satrapi begins to craft a new story. While we’re concerned about Ah’s intentions, he brings Rose to the Kingdom of Sighs, a beautiful place where she is treated exquisitely well. Soon enough, though, she realizes that the tea she’s given every night before bed is drugged and resolves to stay awake to find out why. When she does, she sees a shadowy figure lurking at the door of her room.

Again, rather than veer towards the nefarious as we’d expect from fairy-tale curiosity, Satrapi reveals this figure to be a prince who is in love with Rose and has been keeping chaste watch over her each night. They, of course, fall in love. One day when the pair are walking, she notices a feather under the prince’s arm and plucks it. Here, curiosity holds true to tradition, and plucking the feather causes the prince to die and the land to be stricken.

To atone for her actions, Rose sells herself into slavery (!!) and has a number of adventures in which she must help right wrongs and save the innocent—all of which lead her back, of course, to a way to revive the prince and their love.

That the story has a happy ending doesn’t surprise; after all, it’s been a long time since fairy tales regularly ended on down notes (check out the original Charles Perrault-penned Little Red Riding Hood for a taste of what they used to be like). Instead, it’s getting to the happy ending that’s different.

Curiosity in The Sigh is neither good nor bad, or perhaps it’s both (even Rose’s namesake—a flower that is both beautiful and covered in thorns—suggests as much). Either way, it’s the thing that leads Rose to her most vibrant and wonderful experiences. This is underscored in the art. Nearly all of the book’s first third takes place in Rose’s home, which is illustrated with a series of small drawings strewn throughout the text. This home, the art seems to say, may be comfortable, but it’s also a small, hemmed in world. Once Rose leaves it and enters the Kingdom of Sighs, vibrantly colored splash pages begin to appear, pages whose liveliness and full-bleed reveal the larger world outside her home to be wondrously alive and exciting. Even when the splash pages depict frightening scenes, the verve with which they’re rendered makes it hard to imagine that Rose would trade them and their danger for the sedate safety of her old life. Even though curiosity can put you in dangerous or unpleasant situations, Satrapi says, the chance to live fully and passionately is worth the risk.

By being curious and venturing forth into the larger world, Rose learns that the world is neither all good nor all bad, that curiosity can lead you to many places. It’s a much more complex—and life-affirming—view of the world than most fairy tales allow.

In keeping with modern fairy tale goals, Rose ends up as the most active character, the most able to save people. Instead of being the hero, the prince is relegated to the role of Sleeping Beauty, waiting for Rose to save him.

While there’s a lot to like about The Sigh in revisionist terms, I’m not sure that it will hold up to numerous rereadings by adults. It’s a fun, great-looking book, but it’s a bit slight for anyone other than those truly in love with Satrapi’s work or fairy tales. For those adults with children, though, especially daughters, it’s not hard to imagine The Sigh becoming a household favorite.

Story: 4 / Art: 4 / Overall: 4

(Out of 5 Stars)

This sounds very much like the myth of Cupid and Psyche. I’m interested to see how Satrapi interprets it.

Nice catch, BC1. Sounds very much like Apuleius’ version of Cupid and Psyche (one of the in-set tales in his picaresque novel The Golden Ass), which also has the rights and wrongs of curiosity as a major theme. This work might be a great addition to a course on the ancient novel.