Though he has only a handful of published comics to his name, it could be argued that Michael Chabon owes his career to comics. The author’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, is deeply rooted in the beginnings of the comics industry. Tracing the rise of fictional comic forebears Joe Kavalier and Sammy Clay, the novel cuts to the very core of why creators make (and why fans revere) comics. In the years following Kavalier and Clay‘s release, the characters’ creation The Escapist was the subject of a few metafictional anthologies, as well as a Brian K Vaughan series that pulled out even further, tracking a fictional group of comic creators working to revive the fictional character.

Though he has only a handful of published comics to his name, it could be argued that Michael Chabon owes his career to comics. The author’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, which won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, is deeply rooted in the beginnings of the comics industry. Tracing the rise of fictional comic forebears Joe Kavalier and Sammy Clay, the novel cuts to the very core of why creators make (and why fans revere) comics. In the years following Kavalier and Clay‘s release, the characters’ creation The Escapist was the subject of a few metafictional anthologies, as well as a Brian K Vaughan series that pulled out even further, tracking a fictional group of comic creators working to revive the fictional character.

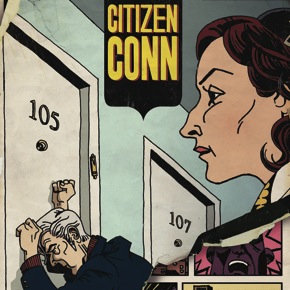

In the February 13 & 20 edition of The New Yorker, Chabon returns to both the form of short story (something he hasn’t written in years) and the subject of creators. In “Citizen Conn,” we find a creative team – artist Morton Feather and writer Artie Conn – that flourished in sixties and now shuffles into old age. The two had a falling out over the rights to their characters, and their friendship never recovered.

It’s a familiar story in many collaborative efforts and especially to comic fans. In an interview with The New Yorker, the author points to two of the most famous names in comics as a source of inspiration.

“Citizen Conn” tells the story of a falling-out between a pair of comic-book creators of the fifties and sixties. Were Mort Feather and Artie Conn based on anyone in particular?

Well, the obvious answer is Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Stan and Jack met in the forties, began collaborating during lean times in the fifties, jointly revived the fortunes of Marvel Comics in the sixties, and then underwent a creative divorce that seems to have resulted in a certain amount of acrimony on Kirby’s side. So the outlines of the story are similar. But Feather and Conn are not Stan and Jack; their fates, their experiences, their biographies, and their personalities are quite different. Jack Kirby died in 1994, still idolized by fans, surrounded by his loving family, as far from the embittered loneliness of Mort Feather as you can be. And Stan Lee is still going strong, a potent creative force who seems to bear up under the tribulations and triumphs of a long and interesting life with the élan for which he has always been famous.

With the news of Tony Moore’s conflict with Robert Kirkman over The Walking Dead, “Citizen Conn” is a particularly timely read.

The story itself, narrated by the female rabbi in Mort’s assisted living home, is written with verve by Chabon. Michael grew up a big comics fan (something he details in Manhood for Amateurs), and there’s a passion evident in his writing whenever he tackles the subject. As in Kavalier and Clay, there’s a convincing backstory laid out that feels as though it exists as a real part of comics history.

When their boss at the barely-surviving Nova Publications intercepted a letter from a competitor that superheroes were going to again surge in popularity, the two were put to work. They “dusted off the long-underwear types,” reviving Nova’s pre-war characters and creating new ones to commercial success. The publisher asked the two to sign away any rights they had to the characters, and there was an acrimonious falling out. Fast forward a few decades, and there’s a push from Artie Conn – the eponymous “Citizen Conn” – to reconcile before it’s too late.

The choice of Rabbi Teplitz as a narrator may seem a strange move, but it’s a smart one. As someone outside of comic fandom, the expository bits on Mort and Artie’s history make sense. As a rabbi, it makes sense that the two Jewish men nearer their end than beginning would open up. It all leads to a story told through conversations that feels painfully real. The seniors are proud, opinionated, smart and stubborn – not too different than their real-world industry veteran peers. It’s easy to empathize with both the conciliatory writer and the bitter artist.

It’s a tale that, by necessity, isn’t a happy one. It’s a story about betrayal, and about forgiveness sought yet not granted. However, Chabon does offer a poignant coda that looks to the first day the leads met in a junior high library. It’s a sad and beautiful moment, and a reminder of why we love comics; though they allow us to escape, they offer us a chance to do it without being alone. It’s also the moment where the connection between “Citizen Conn” and Citizen Kane finally hit me. The story is only a dozen pages long, but it’s stuck with me in a way some of the recent novels I’ve read haven’t managed to. It’s a goddamn great short story.

The New Yorker, being The New Yorker, hasn’t published the story (or an excerpt) for free online. If you’d like to read “Citizen Conn,” you’ll need to either pick up the magazine or buy access on the magazine’s web site. It is, without a doubt, worth the cost of admission.

A great story in general, but a must-read for comic fans. Especially those who love reading up on the history of the industry and the people who started it all.

This story is indeed brilliant. I might recommend you also check your local library if you don’t want to buy the whole magazine. That’s what I did. The New Yorker is one of those titles that many libraries shelve.

This story was great. This plus the rest of the magazine is well worth the cover charge.

I remeber reading Kavalier and Clay and just assumed the two main characters were based on Kirby and Lee.

The closer analog is Siegel and Shuster, but Kavalier and Clay feature traits from a few different creators. Mixed in with a whole lot of fiction.

Thanks for the article. I’m going to go find this.

I recently read this story, which I very much enjoyed – so big thanks to Josh Christie for calling it to my attention. I’ve also gone online and have read people’s criticisms/ponderings about the story’s title, “Citizen Conn.” Some readers have found it too cute, and some find that it refers to the main characters in inaccurate fashion; that if anything, the Mort Feather character – and not Artie Conn – is the one who is being Charles Foster Kane-like, especially while holding onto that school yearbook as his totem Rosebud. If anyone is still reading this thread, and has read the story… what do make of that? And how do you interpret the story’s conclusion?