This is a sort of special kind of review. Our contributor Sam Costello has released a book, Labor & Love: A Garland of American Folk Ballads, with art by Neal Von Flue. I had the idea that it might be interesting to get a different take on this book than the usual post. So we asked Derek McCulloch, writer of the similarly music themed graphic novel, Stagger Lee, a great favorite of both myself and Sam, to read and review the book, which he did. It was bold of Sam to accept and gracious of Derek to contribute. The formatting of the review will be a little different than our normal system, but I hope you’ll forgive the variance.

Labor & Love: A Garland of American Folk Ballads

Written by Sam Costello

Art by Neal Von Flue

$7 print / $1.99 PDF / 44 pages / Full Color

The relationship between comics and music is something I’ve thought about a lot in an on-and-off comics writing career going back 25 years. But while reading Labor & Love: A Garland of American Folk Ballads, a self-published offering from Sam Costello and Neal Von Flue, I was struck by an entirely new thought: from the beginning of the twentieth century to the beginning of the twenty-first, these two media have followed precisely opposite trajectories. That is, folk music was once exactly what its name implies—the music of everyday life, created and performed spontaneously by ordinary people. The street ballads, the field hollers, the sea shanties, and the industrial work songs were gradually consolidated into commercial categories of pop, country, blues, and eventually rock and roll. Songs that had been living, evolving expressions of folk culture for centuries were written down, recorded, formalized, standardized, and commoditized into the music industry we know today. At the same time, comics, an art form that began solely in the hands of a couple of rigidly controlled corporate interests, gradually fragmented into ever greater numbers of smaller niches, with more and more work now disseminated directly by creators, in minis, in ashcans, and on the web. It’s fitting, then, that Labor & Love is essentially a work of folk comics, calling back the time a century ago when there really were still folk songs.

The book adapts four folk staples: “The Wind and the Rain,” “The Wreck of the Old 97,” “The Mermaid,” and “Henry Lee.” The songs are presented here as Americana, representative of what Greil Marcus called “the old, weird America” – though three out of the four actually spring from the older and possibly weirder British Isles. The adaptations of these songs are uncomplicated and straightforward, for the most part simply illustrations of the original lyrics. That is, they’re illustrations of one version of the original lyrics. As is the case with most old folk songs, there are multiple versions to be drawn from, sometimes wildly dissimilar from one another.

Given that (most of) these songs are hundreds of years old and so archetypal as to render the idea of narrative suspense an absurdity, I’m going to freely summarize them here…if you want to avoid spoilers on stories that were old in your great-great-great-great grandparents’ time, skip the next four paragraphs. The first of the stories, “The Wind and the Rain,” is probably of Scottish origin, and comes from a family of murder ballads that tell the same basic story under a variety of different titles—”The Twa Sisters,” “Minnorie,” “Cruel Sister,” and “The Miller and the King’s Daughter” are among the names it’s had over the centuries. Different versions retain different elements of the story, but the one adapted here is fairly comprehensive: a woman loves the miller’s son, but he loves only the woman’s sister. The spurned woman throws her sister into the river to drown. The body floats into the miller’s pond, where the miller’s son, mistaking the billowing white dress for a swan, snags his lover with his hook, piercing her side. In his grief, be builds a fiddle from her bones and the only song it will play is the song of the two sisters. “The Wreck of the Old 97,” the baby of the four songs, comes from the early twentieth century and is an almost journalistic account of a real 1903 train wreck. Pressured by his employer to make up time on an already late schedule, the 97’s engineer maintained high speeds through steep grades and tight curves. The train derailed entering a trestle and plunged into a ravine, killing 11 of the 18 people on board. “The Mermaid” is an old sea shanty about a ship’s crew that has the misfortune to spot a mermaid on a rock. The sailors’ legend has it that the sighting of a mermaid foretells a ship’s doom. The hands gather on the deck to discuss their fate, a storm rises, and down goes the ship with all hands.

Given that (most of) these songs are hundreds of years old and so archetypal as to render the idea of narrative suspense an absurdity, I’m going to freely summarize them here…if you want to avoid spoilers on stories that were old in your great-great-great-great grandparents’ time, skip the next four paragraphs. The first of the stories, “The Wind and the Rain,” is probably of Scottish origin, and comes from a family of murder ballads that tell the same basic story under a variety of different titles—”The Twa Sisters,” “Minnorie,” “Cruel Sister,” and “The Miller and the King’s Daughter” are among the names it’s had over the centuries. Different versions retain different elements of the story, but the one adapted here is fairly comprehensive: a woman loves the miller’s son, but he loves only the woman’s sister. The spurned woman throws her sister into the river to drown. The body floats into the miller’s pond, where the miller’s son, mistaking the billowing white dress for a swan, snags his lover with his hook, piercing her side. In his grief, be builds a fiddle from her bones and the only song it will play is the song of the two sisters. “The Wreck of the Old 97,” the baby of the four songs, comes from the early twentieth century and is an almost journalistic account of a real 1903 train wreck. Pressured by his employer to make up time on an already late schedule, the 97’s engineer maintained high speeds through steep grades and tight curves. The train derailed entering a trestle and plunged into a ravine, killing 11 of the 18 people on board. “The Mermaid” is an old sea shanty about a ship’s crew that has the misfortune to spot a mermaid on a rock. The sailors’ legend has it that the sighting of a mermaid foretells a ship’s doom. The hands gather on the deck to discuss their fate, a storm rises, and down goes the ship with all hands.

“Henry Lee,” the American descendent of the Scots ballad “Young Hunting,” is another murder ballad about a spurned woman. In this case, she vents her rage not on her competitor but on her faithless lover, stabbing him to death and, with the bribed assistance of the town’s women, throwing him in the well. The only witness to the actual murder is a little bird, who taunts the murderess with his knowledge of her guilt. The killer tries to persuade the bird to come closer and live in a fine gold cage, but the bird is clever than the hapless Henry Lee and remains out of reach, ready to sing the guilty secret to the world. As mentioned earlier, all four adaptations simply illustrate the lyrics, avoiding any improvisations or expansion of the stories. In “The Wind and the Rain” and “Henry Lee,” this plays as a strength, but in “The Wreck of the Old 97” and “The Mermaid,” it’s a detriment.

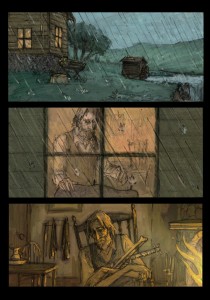

In “The Wind and the Rain,” the thick mood of dread inherent to the song is substantial enough by itself to sustain a story for eight pages. Costello and Von Flue’s adaptation skillfully evokes both the “dreadful wind and rain” that frame the story and the grisly culmination of the miller’s grief. In “Henry Lee,” the most strikingly designed of the four stories, each page features a single full-page illustration partially covered by small inset panels. In his notes on the book, Costello says the intent was to imply hidden meanings underlying the song, and the story very much succeeds in that intent. It’s a very clever use of the graphic possibilities of the comics form.

In “The Wind and the Rain,” the thick mood of dread inherent to the song is substantial enough by itself to sustain a story for eight pages. Costello and Von Flue’s adaptation skillfully evokes both the “dreadful wind and rain” that frame the story and the grisly culmination of the miller’s grief. In “Henry Lee,” the most strikingly designed of the four stories, each page features a single full-page illustration partially covered by small inset panels. In his notes on the book, Costello says the intent was to imply hidden meanings underlying the song, and the story very much succeeds in that intent. It’s a very clever use of the graphic possibilities of the comics form.

“The Wreck of the Old 97” is in my view the weakest of the four adaptations. There’s a one-page set-up, two pages of increasing train speed, then a crash. There’s not really time to build suspense or develop much of an investment in the fate of the train. In the case of “The Mermaid,” what works structurally in a song—each member of the crew in turn discussing their thoughts on their impending demise—is less sound dramatically in a comics story. Both cases highlight the difficulty in adapting from one medium to another. In adaptation, particularly when one has great affinity for the source material, there’s a temptation to stick very closely to the original. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always serve the material or the audience best.

In fact, all four stories really cry out for longer-form adaptations. I’ve considered adapting “The Wind and the Rain” myself—I know it mostly from the version that the British hippy folkers The Pentangle recorded as “Cruel Sister.” —and think it could easily be a longer, more layered piece. Of all, though, I think “The Wreck of the 97” is worthy of novel-length adaptation, what with the complicated social and political conditions underlying the true story behind the song. It’s understandable that they should start out with shorter works, but if Costello and Von Flue are considering taking a shot at something more ambitious, I’d urge them to go with that one. It could have the makings of something on the scale of John Sayles’ Matewan. One of the great things about participating in the folk tradition is the chance to add your own voice to the chorus of centuries.

Labor & Love is available here in both print and digital form, with more on Sam on his website.

Check out Derek McCulloch’s work on his website, including the graphic novels Pug and Stagger Lee.